All content on this site, unless otherwise specified, is © Copyright Ian McGowan / Winged Fist Organization. Web Design Conrad Landais

In 1897, the Greater New York Irish Athletic Association purchased approximately seven acres of land in the suburban farming community then known as Laurel Hill, Long Island. The land was purchased from George Thomson for $9,000, and soon an athletic complex –– Celtic Park –– was built on the Laurel Hill parcel. For the first two decades of the 20th century, dozens of world-class athletes were nurtured and trained by the Irish-American Athletic Club (as they became known in 1904), making Celtic Park one of the premier track & field training facilities in the world, producing more than two-dozen Olympic medalists who, collectively, won more than 50 medals for the U.S. Olympic team. In addition, Celtic Park became a village green for thousands of Irish immigrants. Like many other New York landmarks, it was eventually razed, and in 1930, replaced by an apartment complex bearing the same name.

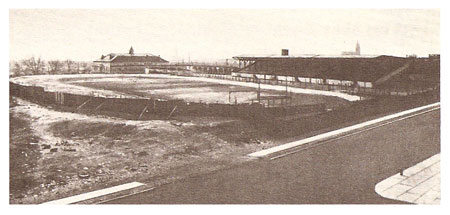

Construction began on Celtic Park in early 1898, in an area that has been referred alternately to as Laurel Hill, Thomson Hill, Long Island, Long Island City, and is today considered part of Woodside and Sunnyside, Queens. (See Maps of Celtic Park). Although the inaugural track meet was held on May 30, 1898 with New York City Magistrate Henry Brann, a native of Ireland, delivering the dedication speech, it wasn't until 1901 that the facility was completed and held its proper public debut. Improvements resulted in the practical rebuilding and remodeling of the stands and grounds, and Celtic Park emerged as one of the most “completely equipped places of the kind about the city.” According to The New York Times, 10 May, 1901:

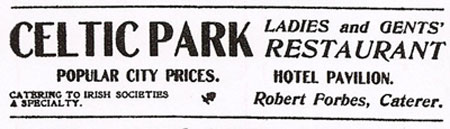

“The entrance to the park is about 600 feet from trolley lines. The clubhouse, including inclosed (sic) piazzas, is 104 by 120 feet, two stories. The basement is 12 feet high and has bowling alleys and sitting rooms for those desiring to watch the games; a restaurant accommodating 1,000 persons, and a kitchen with all the latest improved fixtures. On the floor above are café, dressing rooms, reception room, and private dining hall, which is 80 by 100, but with no posts. On either side are piazzas 12 feet wide by 120 feet. From the piazza may be seen all the games…(and) a big part of Manhattan and other boroughs… On the west side of the grounds are the grand stands, with a seating capacity of 2,500.” ("ATHLETIC FIELD REMODELED.; Celtic Park in New Garb to be Re-opened Monday." The New York Times, May 10, 1901.)

In a sports column in The New York Times in 1934, Robert F. Kelley wrote:

“When one remembers the difficulties under which national and international characters, such as Mel Sheppard, Abel Kiviat, Harry Gissing, Jim Rosenberger, Alvah Meyer, Yank Robbins, Jack Eller, George Bonhag, Lawson Robertson and all the old-timers of that grand old Irish-American Athletic Club, had to train, it is amazing that they were ever able to rise above mediocrity. Celtic Park, out in what was then the wilds of Long Island City, was more inaccessible than Montauk Point is today to a New Yorker. All of these men worked for a living somewhere in New York City, and after an arduous day on the job, took this tiresome trip in order to engage in training.”

Kelley was guilty of slight hyperbole, (the park was close to trolley lines that traveled from the ferry depot at the East River), but was accurate in stating that many of these athletes were “on the job,” as several athletes of the I-AAC were members of the New York City Police Department. A 1916 article in the NY Times asserted that among the 11,000-member police force, at least 4,000 could be classified as athletes and “fully 1,000 could win high athletic honors if they entered the best amateur or professional ranks.” Many of them, of course, did just that, including Detective Martin Sheridan of Manhattan's First Branch Bureau, who won “1,000 cups and as many medals” in his thirteen years of competition. “It was not uncommon for him to win …eight or a dozen cups” during one athletic meet. Other members of both the I-AAC and NYPD included Patrolman Matt McGrath of the Oak Street Station –– “an Olympic Champion, and (held) the world's record for (throwing a) 56-pound weight,” and fellow Patrolman Patrick “Babe’ MacDonald, a traffic cop whose post at one time was 43rd Street and Broadway, who won “more than 1,000 prizes putting the 16-pound shot.” (“4,000 Athletes on Police Force. Majority of New York Patrolmen are in Pink of Physical Condition. Some World Champions.” The New York Times, 17 Jul. 1916: p. 9.)

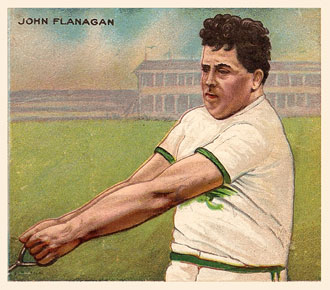

In 1931, following the sale of Celtic Park, Limerick native P.J. Conway, (a founding member of the I-AAC and president for twenty-seven of the club’s thirty-two years of existence), recalled proudly the athletes who trained and competed at Celtic Park:

“Among the athletes who competed were…Martin Sheridan, discus thrower and all-around champion, Matt McGrath, the hammer thrower; now Police Inspector, John Flanagan, our first star hammer thrower; (sic) Mal Shepard, (Melvin Sheppard) middle distance runner; Jack Joyce and John Daly, cross-country runners; John Hayes, the Olympic Marathon champion, and many others well known to the public.” (“Paid $9,000 in 1897 for Celtic Park. City Home Company Bought the Athletic Field Last Year for about $500,000.” The New York Times, 28 Jun. 1931: p. RE10. )

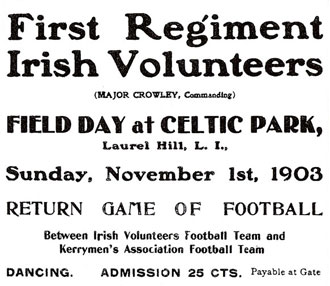

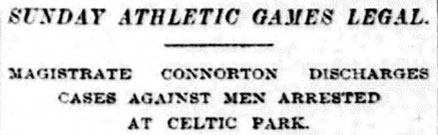

Celtic Park played a pivotal role in challenging early 20th century New York laws that made it illegal to charge admission for a sporting event (or serve alcohol) on a Sunday. These laws were collectively known as Sunday Blue Laws, and Celtic Park served as an unintentional battleground in the fight to change those laws. On numerous occasions, athletes, umpires and managers of Celtic Park were arrested for participating in Sunday games. But this didn't stop Celtic Park games from being held on a regular basis, and eventually the Blue Laws were overturned.

Celtic Park often hosted events governed by the rules of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), the governing body of amateur sports in the U.S. National and world records were frequently set or broken at Celtic Park, sometimes only to be broken again within days or weeks. Celtic Park hosted six AAU All-Around Championships, predecessor of the modern decathlon. And while the decathlon is conducted over two days of competition, the 10-event all-around meet was held on a single afternoon. The 1902 all-around was won by Adam Gunn; 1903 by Ellery H. Clark; 1907 by Martin Sheridan; 1908 by John Bredemus; and, in 1909, again by Martin Sheridan. The final AAU All-Around Championship at Celtic Park was held in 1912 and won by Jim Thorpe, fresh from his Olympic titles at Stockholm.

The Gaelic American, published by John Devoy and owned by Daniel F. Cohalan, was the unofficial newspaper of the Clan-na-Gael. As an incentive to sell subscriptions to the paper, The Gaelic American offered a “Brand New Mauser Rifle, with Short Knife-Bayonet and Fifty Rounds of Ammunition, delivered, express paid, to any address” for anyone selling fifty subscriptions or more.

Cohalan was a lawyer, a jurist, and in effect the in-house counsel for the Clan-na-Gael. He also served as a member of the Board of Directors of the I-AAC as early as 1903, the chairman of the Martin J. Sheridan Memorial Committee in 1918, and was the attorney who handled the sale of Celtic Park in 1930. For nearly thirty years, Cohalan was intricately involved with the Celtic Park and the I-AAC, and for most of this time he was also involved with the clandestine operations of the Clan-na-Gael. “It was no secret that Cohalan and the old Fenian soldier Devoy stood at the head of the Clan-na-Gael, the most intransigent of American fighters for Irish independence; and there was little doubt that they were the American sponsors of the Dublin Rising, (and) that Roger Casement was in effect their agent.” (Reid, B.L. The Man from New York: John Quinn and his Friends. Oxford University Press, New York. 1968: p. 324).

“Irishmen are responsible in a large degree for the healthy athletic influences now prevalent in American cities. The first centenary of the Irish Revolution of 1798 was remarkable as being the year which saw the birth of the Irish-Ireland Movement and the sweeping of the last vestige of an old world tyranny from the American main. The Spanish War was insignificant compared to the foundation of the athletic America, which can honestly be claimed by the men who conceived Celtic Park… The formation of the Public Schools Athletic League, the Catholic Athletic League, the Military Athletic League and the Irish Counties Athletic Union can be traced directly to Celtic Park.” (“Irish Athletes Made Splendid Records.” The Gaelic American 8 Feb. 1908: p. 1).

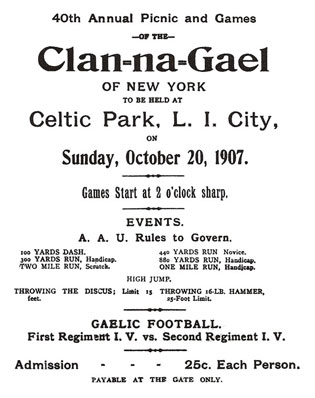

From as early as 1905, until at least 1921, Clan-na-Gael held fundraisers, picnics and athletic events at Celtic Park. At these events that attracted thousands of Irish exiles and Irish-Americans, Clan-na-Gael publicly advocated armed resistance to British occupation of Ireland well over a decade before the Easter Rising.

In 1914, at a secret meeting held in New York, a delegation from Clan-na-Gael met with the German Consul General, Count von Bernstoff and German spy, Wolf von Igel, to discuss Germany’s support for an armed insurrection in Ireland. “The Clan delegation told von Bernstoff bluntly that a revolt would take place in Ireland sometime soon, while Britain’s soldiers were involved on the Western Front. They had come not to ask for money – the American Irish would provide cash (emphasis added) – but for the promise of German arms and officers when the time came for the IRB to rise and strike their preoccupied foe.” (Golway, Terry. Irish Rebel: John Devoy and America’s Fight for Ireland’s Freedom. St. Martin’s Press, New York. 1998: p. 198).

On September 23, 1917, a front page headline in The New York Times read: “Cohalan and Other Irish Leaders named in New Exposé of German Plots: Von Igel Papers Bared Wide Conspiracy.” The federal Committee on Public Information released an “official exposé” of “German intrigue” in America;

“. . . prominently involving, on its Irish side, Judge Daniel F. Cohalan of the New York Supreme Court and John Devoy of The Gaelic American. The events described were a year and a half old, coinciding (hardly by chance) with the Easter Rising in Dublin and long antedating America’s formal entry into the war. According to the account, Secret Service agents in April 1916 had raided an ‘advertising office’ in Wall Street and had trapped a Nordic giant named Wolf von Igel in the act of trying to destroy papers which showed numerous acts of complicity between German agents and American sympathizers aiming at sabotage and general troubling of the sentiment for Allied unity. Among the ‘documents’ was a copy of what purported to be a message from Cohalan to Count von Bernstoff, the German ambassador and super-spy, dated April 17, 1916, a week before the Rising, advising the Germans to bomb the English coast, to land arms and officers in Ireland, and to seal off the Irish ports from English access: to promote the rebellion and to help accomplish the eventual defeat of Britain.” (Reid, p.223-224)

The scope of this article does not allow space to explore all of the intricacies of the activities of Daniel F. Cohalan, John Devoy, Roger Casment and the Clan-na-Gael’s involvement in the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, but it does appear that a significant portion of the money that the Clan-na-Gael raised to finance the Easter Rising came from the 25 cent admission charged at the gate of Celtic Park.

The Decline of Celtic Park

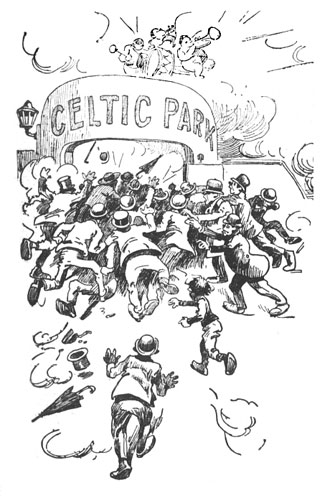

There were a few major factors that combined to contribute to the decline of the Irish-American Athletic Club and popularity of Celtic Park. The initial factor was the advent of World War One. Commenting on the impact of the “Great War,” P.J. Conway said, “We decided to give up athletics for its duration. We wrote to President Wilson and offered Celtic Park to the nation for any purpose he saw fit. He thanked us for our patriotism but he had to decline the offer. After the war it was impossible to gather the old crowds together.” In this interview, however, Conway neglected to mention some other reasons crowds didn't return –– including adoption of the Volstead Act of 1920. It’s clear that the decline of Celtic Park was hastened by Prohibition –– a 13-year ban on the sale of alcohol in the United States. It didn’t take Celtic Park long to gain notoriety for the illicit sale of alcohol, so it quickly became a high-profile target for law enforcement scrutiny and the object of unflattering media reports. Illicit sale of alcohol –– and the resulting violence that ensued from police raids –– brought intense surveillance of Celtic Park activities. “For more than six months alleged bootleggers have been arrested at the park every Sunday, sometimes as many as a dozen men being taken into custody. These men have been doing a retail business from bottles of whiskey carried in their pockets,” it was charged. (“Celtic Park Under Prosecutor’s Fire. Queens District Attorney to Investigate Riot Sunday in which Four Were Shot.” New York Times 25 Jul. 1922: p. 12.)

Greyhound Racing

As new, more modern facilities were being built in the NYC area, a decline in popularity of Celtic Park as a venue for athletic competitions forced the club to find other income-producing events. From 1928-30, on the same track where Olympic gold medalists had once performed before thousands of cheering spectators, greyhound races were held. And in tribute to a bygone era, track promoters included a race where the winning dog owner received the “Martin J. Sheridan Trophy,” named in honor of the I-AAC’s great Olympic champion. But greyhound racing at Celtic Park didn't last long, in large part due to pressure from the growing residential community:

“George W. Morton Jr., President of the Laurel Hill Improvement Association, announced…that his organization had united with the Thomson Hill Taxpayers' Association in an effort to prevent the holding of greyhound races in Celtic Park, Laurel Hill, Queens. He said the races would be a detriment to the community, since only a gambling and 'riff-raff' element would be attracted by them.” (“Protest Greyhound Races. Laurel Hills Associations Ask Patten to bar Park Contests.” New York Times 21 Sept. 1928: p. 26).

Sold for Housing

In 1930, after more than thirty years as a meeting place for the Irish in New York, and training grounds for world-class athletes, Celtic Park was sold to the City and Suburban Homes Company for the construction of apartments for working-class families. The plot was irregular in shape, as it was originally acquired before the streets were laid out. To adjust for the property’s irregular shape, City and Suburban Homes Company had to acquire additional plots from separate owners in order to have two full square blocks, 190’ wide by 600’ deep:

“These blocks lie between Forty-second (old Madden) Street, and Forty-fourth (old Locust) Street, and Forty-eight (old Anable) Avenue and Fiftieth (old Gould) Avenue with Forty-third (old Laurel Hill) Avenue dividing them. Old-timers state that the section was known in early days as Thomson Hill. It was decided to develop the two rectangular plots with modern apartment houses, attractive in design, thoroughly up to date in equipment, spacious in size of rooms and yet within the means of the wage earner in rental.”

(Big Housing Plan for Celtic Park..." New York Times 7 Jun. 1931.)